Why doesn’t it feel that bad? (2/5)

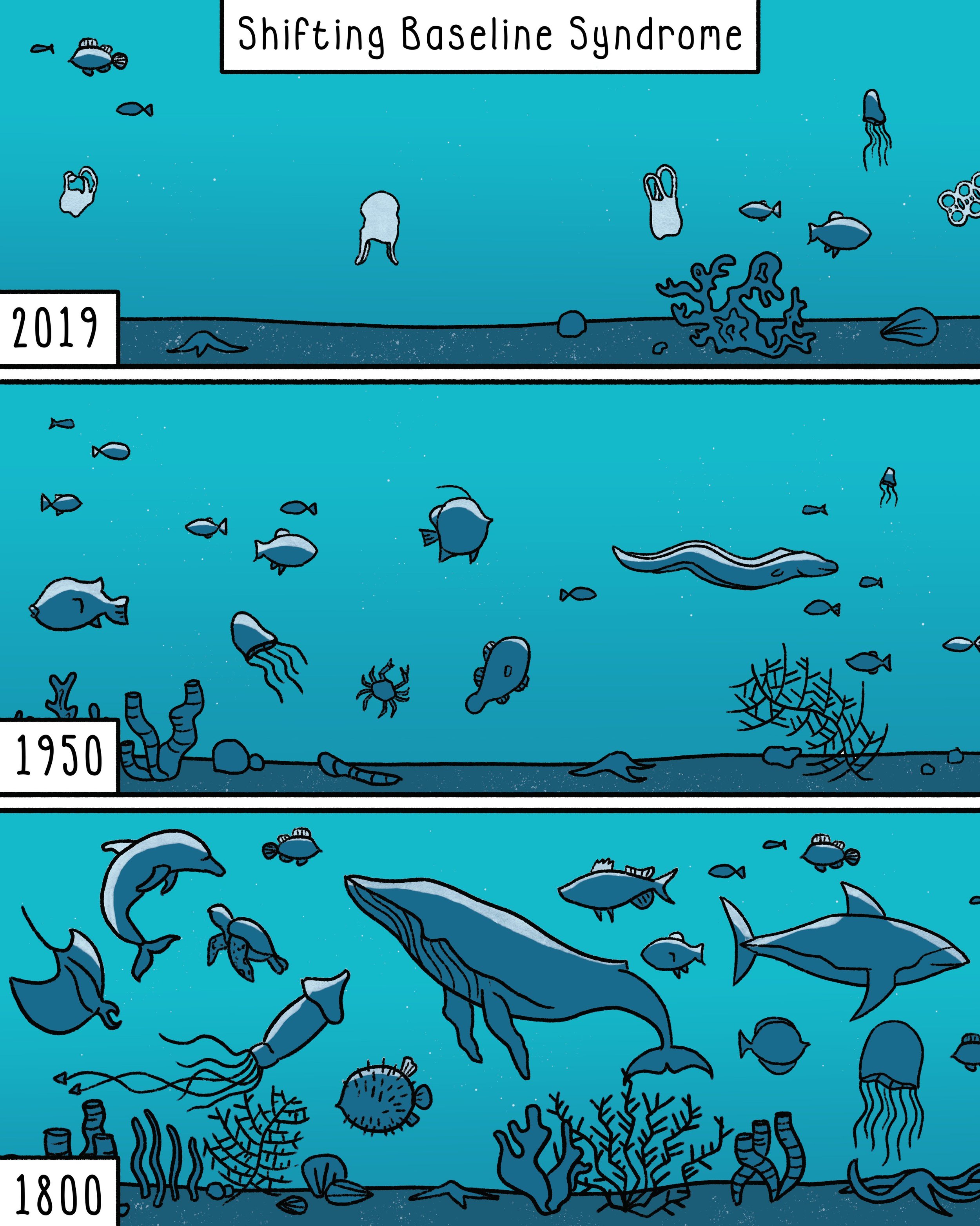

An illustration by, Cameron Shepherd. Source

Although we feel the degradation of the natural world around us to a degree, why are we not in a complete state of collective shock & grief at this staggering loss? This is best explained by a phenomenon known as ‘Shifting Baseline Syndrome’, which explains that due to short life-spans and faulty memories, humans have a poor conception of how much of the natural world has been degraded by our actions, because our ‘baseline’ shifts with every generation. In essence, what we see as pristine nature would be seen by our ancestors as hopelessly degraded, and what we see as degraded, our children will view as ‘natural’.[1]

This is a particularly pernicious cycle, not least because humans are story tellers. We use personal & cultural experience to create a narrative to help explain our place in the world, which in turn guides are actions. For example the concept of money is little more than a story we all believe which gives value to pieces of paper, and now digits on a screen. Our story gives the paper value, but without a human to do that, the objective reality of that piece of paper consigns it to being just paper. Most stories are not fact-based, but based on cultural shared experience, which becomes concerning when our perceptions are deceived. This is relevant to shifting baseline syndrome, because the phenomenon blinds us to the true scale of loss, which means that the stories that we tell ourselves about our relationship with nature do not reflect the true scale of the problem. We see this in the overriding Western narrative that we are inherently separate to our environment and that the natural world is infinitely abundant and designed for our use. This narrative is leading to our undoing.

“And so the story of loss continues, in a seemingly unstoppable spiral of degradation, slow enough to insidiously slip past us, but fast enough to pose an existential crisis for humanity.”

The perception problem is further compounded by the limitations of the data we have on biodiversity loss. You may have noticed that almost all time-bound comparisons go back to 1970, which is when the best comparable data sets go back to. Naturalists have of course recorded the natural world for centuries, but most observations tended to focus on species identification, rather than species abundance.

To look back further than 1970, we have to rely on written descriptions of the natural world. From the literature, we see an Earth unfathomably abundant when viewed from our current day perspective. George Monbiot describes this well in his book, Feral, quoting Oliver Goldsmith, who in 1776 described the arrival of migratory herring as, ‘divided into distinct columns, of five or six miles in length, and three or four broad, the water before them curls up, as if forced out of its bed…the whole water seems alive; and is seen so black with them to a great distance, that the numbers seem inexhaustible.’ Such a sight which awed Mr Goldsmith 247 years ago may well have seemed normal, or even degraded, to his ancestors. And so the story of loss continues, in a seemingly unstoppable spiral of degradation, slow enough to insidiously slip past us, but fast enough to pose an existential crisis for humanity.[2]

[2] Feral, page 231, George Monbiot